Our Earthship Experience:

So, what exactly is this thing?

Christened an “Earthship” by designer/architect Michael Reynolds, literally hundreds of these homes (made primarily from old automobile tires and beer cans) have been constructed in the southwestern U.S. This project was the first Earthship constructed within the state of Ohio.

The Earthship concept is pretty cool – homes that take advantage of the natural heating and cooling properties of the earth, passive heat from the sun, discarded and problem waste materials and then mix these together with a vision towards protecting the environment. The result is a comfortable and peaceful place to live. If you want to find more background on the concept (and a whole lot more), check out the source at www.earthship.org.

Our Experience

After attending a workshop put on by Solar Survival, reading all the books, and purchasing a set of generic blueprints… we were ready to go. We decided to give this thing a try, taking our vast background in construction (in other words… none at all) and figure it out as we went along. It became our summer project for a number of years. But work was not steady. Our progress was constantly interrupted by work. And then we went and lived a few years in Europe. We eventually returned to the US in the autumn of 2004 (a bit reluctantly) and steadied ourselves to finish this project. This was the beginning of Blue Rock Station.

Back sometime in the early 90’s, Annie was listening to our local radio station in Tampa (a great little community radio station called WMNF) to an interview with Michael Reynolds describing an interesting house he had designed for actor Dennis Weaver. She looked into it a bit, then suggested we consider building one on some property we owned in Ohio. Foolishly I nodded my head and soon found myself in Taos, New Mexico – out in the middle of the desert pounding dirt into old tires.

So just how do you go about building an Earthship like this? There are a lot of great web sites out there that do a terrific job in describing the process. There are also a number of books available that are quite helpful if you want to go further, but since you are here – we put together a fairly basic overview to give you a taste:

Pounding the tires…

We all know the problem… hundreds of thousands of tires fillings landfills for generations to come. Nobody pretends that Earthships are the sole answer, but they are a great way to put thousands of these eyesores to good use.

We used about 1,400 tires in the initial construction of our Earthship.

The tire itself is little more than a mold to hold rammed earth in place. It generally takes about two wheel barrow loads of earth to fill each tire. Simply take the stuff that has been excavated from your site, shovel it into the tire and spend the rest of the summer swinging a sledge hammer.

Many people ask if there is any regulatory issue (or code issue) in using the discarded tires. I suspect it varies greatly from place to place – but here in Ohio at the time we were building, we were required to contact the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) since we were going to use more than 100 tires (less is apparently not regulated). The folks there were great to work with and actually provided us with the tires from an illegal dump site. They visited several times to make sure we were storing the tires properly (avoid mosquitoes) and even helped pound a few. Someone was kind enough to share the current regulations, so we will share them here with you.

Beneficial Use of Tires (from the Ohio EPA, GD #671)

After a couple of tires, you will find you develop your own style. Most people end up pulling the inside rim of the tire up with their hands and shoving the loose dirt into the tire. Then you begin pounding with the sledge.

Once filled to the brim, level the tire to itself and in respect to the tires around it. If you do this right, the entire wall should end up standing straight and tall.

The good folks at Solar Survival don’t seem to suffer from some of the same difficulties we encountered during this phase of the project. We were told that they often have so many volunteers showing up on site, that they interview them and only accept those that show promise.

We, on the other hand, placed ad after ad in the local newspaper trying to get anyone who could swing a sledgehammer to come out and work – and we even would pay them, with Catlyn supervising.

Admittedly pounding tires is really hard work, but we still managed to go through about 60 “strong young men” during the course of the summer (in an effort to keep 3-4 working at any one time). Some lasted less than a day.

Surprisingly we found the people who lasted longest and did the best work were middle-aged men and young women. I don’t know what that says about anything… but I thought I would throw it in for all to ponder.

Laying the Foundation…

After selecting the suitable site, you clear your patch of heaven and lay out a rough image of the Earthship’s footprint. All that dirt and clay and rock that is being scraped away is what you will use to fill those hundreds of tires.

The house “floats” on this foundation – which typically causes traditional builders to cringe (they want to build deep footers). I am perfectly happy to buck conventional construction wisdom (as I know no better). Fortunately we did not have to put this theory to the test as we were resting on bedrock after scraping off the topsoil.

One thing that the experts (Earthship experts that is) recommend is that you pile your earth right in the middle of where you will be working. This is good advice, saving miles of pushing a wheelbarrow around before your project is finished.

Of course you need to be very careful in placing your first layer of tires, as everything keys off these. Measure and check and double check and measure again.

Then you just keep building up the courses, ensuring they are level and solid. It is also a good idea to level them vertically as you go, avoiding future work when it comes to mudding.

The Earthship’s roof…

Perhaps one of the trickiest challenges we faced in this construction project was to build a roof that didn’t leak. Since Earthships were born out in the desert southwest, I suspect the folks out there didn’t give it much thought. But here in wet southeastern Ohio, it is a major concern. The unique “V-shaped” design of the roof is especially vulnerable. So take great care.

We have struggled with leaks now for 20 years. If I had it to do over, I would not have incorporated the “V” shaped roof, opting for a simple shed roof design, highest in the front, lowest in the back. We finally seem to have solved the problem (all metal and ultra flashed) – but it has been a royal pain in the butt.

Once you have finished pounding tires, you must then build a sill plate that binds the top row of tires together. How you do this is outlined in the Solar Survival books (and you thought you were going to learn everything you needed to know from this site, eh?)

The composite “I-beams” span the gap created by the “U-shaped” tire walls. Some folks will use felled trees as rafters – which gives a very rustic appearance. Just remember the span is quite wide and the beam needs to support a great deal of weight.

In the center of that trough, you must build a “cricket” that sheds the water off in both directions. Our design (the basic plan from Solar Survival) has two cisterns that catch the water from the roof, one on each side of the main structure.

In each of the three rooms, we have placed a skylight. These are essential (in our view) as they provide a tremendous amount of light. But they are also a pain – being the weak point where most of your leaking will occur. Be prepared to do plenty of flashing around them. We also coated the entire roof with a Neoprene rolled surface, then covered this with salvaged slate (reclaimed from those old barns we tore down).

And of course, insulate your roof well. We used rolled insulation in the face and blown-in insulation in the main rooms. The Earthship is remarkably snug. We have found that even in temperatures of – 15° F the house stays at 55° F or more, even without a heat source. When we light the wood stove, the entire house is soon around 70° F.

Building the face…

The face of the structure (or greenhouse area) is the passive solar heart source of this building. In order to gather in the maximum amount of sunshine, the entire structure must be oriented to south-south east (assuming you’re in the northern hemisphere).

The face is also angled based on your latitude, so that on the winter solstice it is at a 90 degree angle to the sunlight (at 40 degree N we positioned it at a 50 degree angle, at 45 degree N you would position it at a 55 degree… and so on). Our experience has shown this whole angle thing is really necessary and causes a number of problems. So stick with straight up-and-down windows.

When we got ready to do this phase of the project, it seemed a bit overwhelming. So we tried to get some “professional” help – but were soon put off by the price. Eventually we were able to do the job for about 1/10th the best estimate. As you can see, we even managed to get it to look somewhat like the diagram.

Actually, the construction of the face is fairly straightforward. You build a wooden frame onto a foundation of pounded tires, setting it at the proper angle and securing it to the main structure roof with really heavy-duty rafters. The wood we used was mostly salvaged from local barns that we dismantled (arranging with the farmer to salvage the wood before he burned them down).

There are some fairly complicated methods for constructing the large windows… but we took the lazy way out. We purchased a number of patio doors from a warehouse (these were returns and seconds). In this way we avoided a lot of problems with leaking that we read about on various web sites. We had the windows delivered before we began framing the face. I have read of problems some people have had matching custom windows with the openings, but we avoided this by having each window right there on site and checking and double-checking before hammering in that final nail.

After securing the patio door panels in the various slots, we constructed three “dormers” where we could place traditional windows that open. This is simply a matter of taste and we have seen a number of Earthships that skip this step entirely. By doing this, you lose a bit of sunlight, but we placed them in the bathroom and the utility room – so good ventilation was more important to us than passive solar heat in these locations.

By design, the face takes the full brunt of all the elements the world will throw at your Earthship. It intentionally takes as much direct sunlight as possible, as well as all the wind, rain and snow your locale can dish out. So worry a lot about drainage and waterproofing.

We addressed this problem by encasing the entire face in coated aluminum, using a gutter break to fit each piece. If you don’t do something like this, the different expansion/contraction rates of the various materials will open up micro cracks and water will find its way into your snug little home.

Managed to fix the front leaking issues by building an awning over the entire face. Not in the original architectural plans. Seems to work quite nicely and does not cut down on heat or light.

The Wetlands, your indoor garden…

The wetlands are an important part of the Earthship concept. All the wastewater (other than the toilet) drains into these structures and is used to grow your indoor garden. Excess water can even be filtered through the wetlands and used again by pumping it back into the cistern. Although we get enough rain that this has never been necessary.

The walls of the wetlands are built using old cans or bottles, these serving as air gaps in the concrete leaving a very strong “honeycomb” support structure. The plumbing drains are then fed into the wetlands at one end, the unit sloped away so that water entering will flow downhill (through a mixture of stone, sand, charcoal and dirt) being purified along the way.

Our home has two wetlands, one at each end of the “face” area of the building. One receives the water from two sinks and the shower – the other from the kitchen sink and the washing machine.

The above grade surface of the wetlands walls can be finished as you like. Typically these will receive a smooth adobe finish similar to those of the interior walls.

Building a can wall…

The interior walls of our Earthship are all non load bearing, so there are quite a few options. Our walls are constructed with old cans and bottles, along with cement or mud (depending on the amount of water that will be present – for example we used cement in the shower area).

We built these walls using two main styles – a framed structure (building the frame out of wood and then filling the cavities with the can wall) or free form (just building layer upon layer of cans).

The first step is to create the “mud” – a mixture of sifted clay (from on site), sand and a bit straw and water. Then, nail a few bits of plaster lathe to the wood frame. These will help anchor the can wall to the frame.

Lay down a layer of mud, pressing cans into it. Repeat the process, filling mud between and on top of the cans. It’s a good idea to squeeze a small dimple in the middle of the can, so it is no longer perfectly round. That way you cannot “pop” the can out of the dried wall.

At the appropriate level, you press the lathe into the mud, anchoring the wall. You will find you can only do a few courses before it begins to feel a bit unstable – at which point you just let the thing dry before continuing.

After you build up the wall, and it is dry, you can begin to finish the exterior. In our case, we finished the walls with a mud mixture. We will talk a bit more about this process in the section of this web site that demonstrates how to finish the interior tire walls.

Finishing an interior tire wall…

The tire wall is the “heart and soul” of the Earthship structure. This feature, probably more than anything else, gives the home its unique look and feel. When you tell folks about the home, this is the thing they have the hardest time visualizing. So let’s take a look at what you do to finish off the interior wall.

You begin, of course with the pounded tire wall. The electrical lines are simply mounted on the exterior of the tires with staples. Slowly fill in the cavities between the tires with a mud/sand/straw mixture, pressing in empty cans to fill in the bigger spaces.

You don’t have to be dainty at this stage, and can sling as much mud as will stick (sounds like a Louisiana politician). Anyway, the goal here is to build the entire section out so that you have a relatively flat surface.

Next comes the “rough” coat. Without getting too bogged down in details, the various coats require a slightly different mix of the mud. The scratch coats just create a uniform coated surface. Scratch up the surface while the mud is still wet, so the following coat will adhere well.

There are probably as many ways to mud a wall as there are people, and you will no doubt find your own path. After you let the surface dry, wet the wall with water, then apply the next layer to the wet area. I found it most comfortable to use a spray bottle and a mortar board with pointed trowel – but some of the guys found it easier to just use a bucket of mud and spread it with their hands (until the final coat, anyway).

As you build out the wall, you will incorporate the wiring as well as the outlets and switches. Below you can see an outlet box (the mud wall will be built out to level… and we will clean off all the mud, don’t worry) as well as a switch (where the wall has already been built out).

Plumbing systems…

Our water supply comes from collecting rain from the roof. The original design called for 2 – 5,000 gallon cisterns (one on each end of the house).

We have operated for 15 years with only one cistern finished and functional without problem – so we figure one cistern is probably enough given the large amount of rainfall we receive in this part of the country. So we knocked a door through the wall of the other cistern (not an easy task) and turned it into a root cellar.

The water is then pumped from the cistern to a pressure tank. All this is relatively conventional. In fact, we had a regular plumber create the system and it was fully inspected and approved by the local authorities.

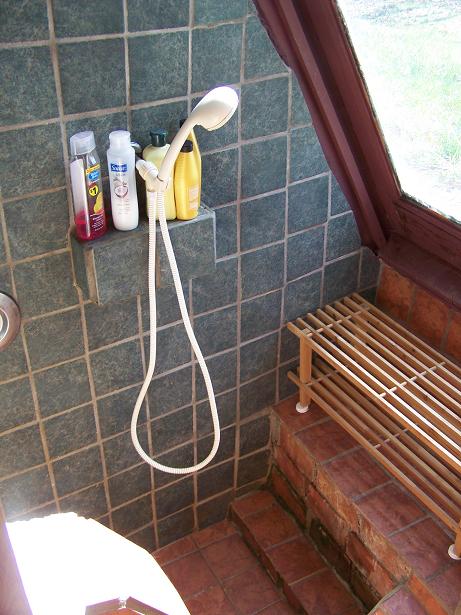

We decided to create a shower room separate from the toilet area (European style). The walls of the shower are made of cans and bottles, then coated in concrete, and then tiled.

Heating systems…

Our Earthship uses three methods (in tandem) to heat our home. These include:

Thermal Mass – the earth itself provides the lion’s share of of the heat (and a bit of cooling in the summer). If you have ever been in a cave, you will know that the temperature feels cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Typically they stay about 56 degrees F year-round. The earth rammed into the tires, plus the earth mounded against the north side of the building keep the temperature in the home at least 50 degrees F no matter what the outside temperature may be. During construction, we noted one day when the temperature was -14 degrees F outdoors, inside the temperature was 50 degrees F with no sun and no additional heating source.

Passive Solar – the orientation of the home, facing just east of south is key in generating heat within the house when the sun is shining. The angle of the glass is designed to maximize solar gain during the winter solstice (and the weeks surrounding it). Based on latitude, our windows are angled at 50 degrees as we are at 40 degrees N latitude (take 90, subtract your latitude and you will find the angle where the sun will penetrate at right angles on the solstice).

We have found that too much sun, rather than not enough is the major problem on sunny days. If we had it to do over, we would have placed the windows vertically to avoid leaking (windows are just not designed to be placed at an angle).

But the passive solar gain is impressive and the house warms up to 60 – 70 degrees F when the sun is shining, regardless of the outdoor temperature.

Wood Stove – we have one wood burning stove that supplements the heat. This is located in the living room. Since we have about 30 acres of woodlands, securing firewood is easy and free (aside from the sweat and cursing). Running this wood stove will raise the heat in the living room to the mid to upper 70’s. We installed a bathroom vent fan at the highest point in the living room, sucking hot air into the center “U” when turned on. There is a second fan installed in the center “U” that can draw air into the third “U”. This provides additional heat as well as allows us to move the air around within the home.

Finishing the thing…

It seems that the finish work takes forever. One thing to remember in any building project is that it will take twice as long as you think it will and cost twice as much.

In keeping with the concepts of an Earthship, we have tried our best to use what is available locally.

We happen to live in rural Appalachia and so there is plenty of old barn wood (local farmers seem to like to burn them down), slate and assorted other bits and bobs.

We have made our own cabinets and shelves from the barn wood. Each winter I sign up for a cabinet making class at our local high school – which gives me access to their workshop that would make Norm Abrams green with envy.

The roof is metal, as will be the floors (we have constructed slate floors on other projects and they are absolutely beautiful. In one of the rooms we also put in a recycled barn wood floor.

We managed to buy heavy industrial stainless steel counters for our kitchen at auction (when they tore down a local school – we do a lot of tearing down around here and not much building up). Other sinks and materials we bought at various auctions and a habitat store in Columbus, Ohio.

Must admit, we got better at things as we went along. Probably best to just get things working and in place, then refine them as you gain the skills. People often ask us how long it takes to build an Earthship. I guess we will let you know when we finish.

We also managed to find some old pressed tin for the ceilings – bought for almost nothing from a guy who raided a demolition site 30 years ago – salvaging the tin but then never using it.

If you wander the web looking at Earthships, you will find that most are located in the western US and reflect that building style. Our home is quite different – reflecting our locale. You will also find that many of these homes cost a bundle. Ours was constructed on the “cheap” using mostly scrounged or salvaged materials (as it should be, he added smugly).

ReUse and RePurpose

We tried to use as many salvaged materials as possible. We reclaimed a lot of barn wood, and found various bits and bobs at Habitat stores (like the counter in the entrance). We also used a bit of old slate to make a nice looking floor.